The Huron House and St. Clair Hotel Properties

(311-323 Huron Avenue Historic Property Uses, to 1990) [1]

By Vicki Priest, MA History December 5, 2019

Port Huron was once home to a decent number of four- and five-story brick and stone structures [2], one of which, the Harrington Hotel, still exists. Coupled with wonderful electric and water-based mass transportation (locally and to Detroit), one could easily argue the period having this built and cultural environment—roughly the late 1800s to the early 1900s—was the Golden Age of Port Huron.

The Huron House along Huron Avenue for many years was one of those five-story buildings (perhaps the first one). The earliest photograph identified in this study shows an early iteration of The Huron House as a wood 2 ½ story structure. It was vastly enlarged as a 4- and 5-story building in the 1870s, and for whatever reason the 5-story section was reduced to 4-stories in the very late 1800s. At this time it became the St. Clair Hotel, which met its demise in a fire of 1903. The history of this hotel, and later uses of 2/3 of the former hotel’s properties (313-317 Huron Ave.), are very briefly provided below. The current research was limited to 1990.

1860s to 1903: The Huron House hotel/St. Clair Hotel

The earliest source of information on the properties (so far) comes from a photo of the Huron House labeled as “circa 1860” in a local history book. It shows the wood Huron House along Huron Avenue, and a brick structure next to it that very much appears to be the bottom half of the later five-story portion of the brick Huron House (Port Huron: Celebrating Our Past, 2006, p 117), discussed more below. Considering that a different Huron House building existed at the northeast corner of Huron Avenue and Butler Street in 1859, 1860 would be the earliest year that the Huron House in the photo could have existed.[3]

The first known city directory for Port Huron dates from 1870 (copyright) and 1871 (publication year). From this directory we know that the Huron House existed within the current 300s block of Huron Ave, west side, even though its addresses were different than today’s (they were all even numbers from 50 to 58; directory pages 4, 50, 93, 99). An 1867 bird’s eye view map of Port Huron (A. Ruger, LoC) shows a substantial 2-story building in the center of the block.

In 1873 and 1874, the operator of the Huron House, Mr. George Knill, basically built (or rather managed the construction for investors [4]) a new huge and “magnificent” hotel—one of the largest in Michigan at the time. According to the CPI Inflation Calculator, the owners’ $75,000 investment is equal to $1,604,744 in today’s currency! The brick hotel was a handsome one, having a five-story center that contained a courtyard, and 4-story wings on either side. This hotel took up the addresses of what is now 311 – 321/323 Huron Ave (The Port Huron Times 09-26-1873, p 4; 12-04-1873, p 4; 09-01-1874, p 4).

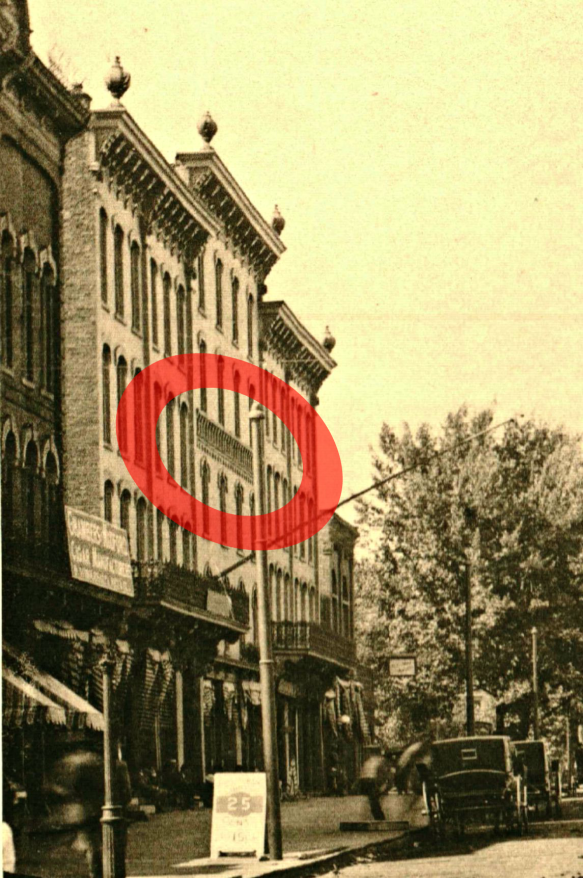

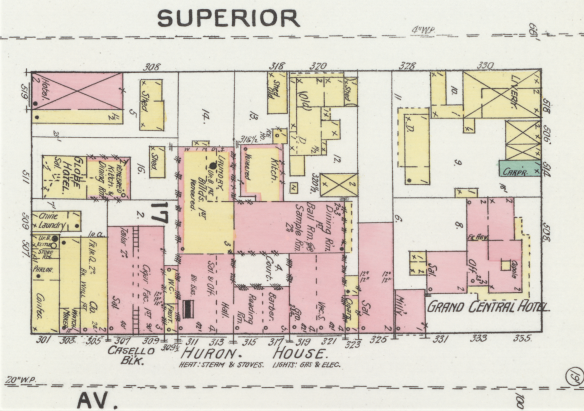

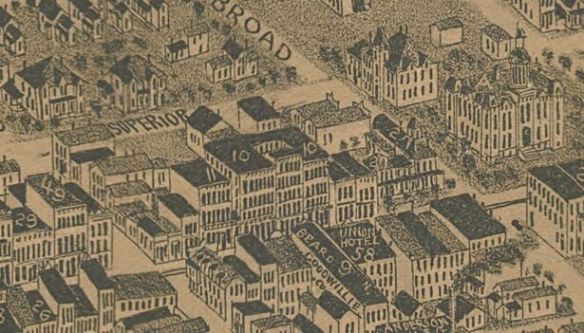

A sidelong view of the hotel can be seen in a photo showing a Huron Avenue street view in The Artwork of St. Clair County, 1893 (no page number). When looking at both this photo and the one mentioned earlier from circa 1860, one can see the resemblance of the brick structure to the north of the wood hotel with that of the taller 1873 center portion of the hotel. The windows and the decorative brickwork are the same. See Figures 1 and 2. The 1892 Sanborn Fire Insurance map (Figure 3) shows a large wood structure—so the original Huron House—attached at the back of the south wing of the brick 1870’s structure. This confirms what a contemporary newspaper article (Port Huron Times, 12-04-1873, p 4) stated about the wood structure being saved and moved to the back of the newer hotel building. Besides the Sanborn map, an 1894 birds eye view map of Port Huron shows the basic configuration of the hotel with courtyard (C. J. Pauli, LoC). It dominates the block, and indeed the area, with its scale (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Huron House (at left), circa 1860, from page 117, Port Huron: Celebrating our Past (2006). The red oval points out decorative brick and window placement that appears to be the same found in the later center portion of the brick Huron Hotel (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Sidelong view of Huron House, as published in the 1893 (unpaginated) book Artwork of St. Clair County. Red oval indicates features seemingly shared with earlier brick structure.

Figure 3. 1892 Sanborn Fire Insurance map (page 6 portion; Library of Congress). Note the wood portion, in yellow, which was the original Huron House.

Figure 4. 1894 bird’s eye view map of Port Huron, showing the area of the Huron Hotel (indicated by the number 10). The number of windows is not accurate. (C.J. Pauli map on file, Library of Congress).

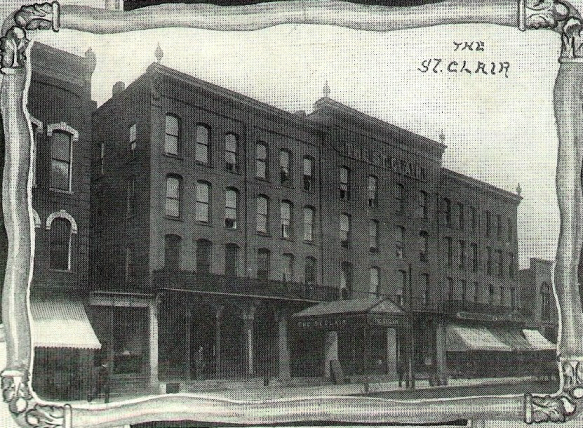

In early 1898, after undergoing $15,000 worth of repairs, the Huron House became the St. Clair Hotel. The proprietor was the same Mr. Knill at this transition, although he no longer held that position in 1903. A photo of the hotel, Figure 5, from a 1900 publication shows a significantly altered middle section. The fifth floor was not only removed, but the windows were made to line up with the window placement of the wings; the windows themselves were changed to one-over-one sash windows, instead of four-over-four sash (the old style can still be seen in a side wall of the hotel). The decorative brick work is now gone, and the window hoods of the entire front facade had been removed. It’s interesting, though sad, that it was thought better to transform the building’s appearance to a plainer, starker state.

Figure 5. The St. Clair Hotel as shown in W.W. Black’s 1900 book, Port Huron: A Souvenir in Half-tone, page 11.

In February of that year the hotel, along with other neighboring structures, were tragically destroyed by fire. The hotel was not the only business within the structure (back then, large structures were referred to as “blocks”). Small businesses had operated out of it too, like the confectionery store where the fire may have started (a witness said he saw the fire start there, but the store owner said the oven hadn’t been used that day). The International Tea Store and Asman Floral Co. were also within the hotel block. These businesses were at 319 Huron Ave, and it was in the basement of this part of the hotel that it was thought that a hotel employee, Albert Wortley, lost his life in the fire (his body, apparently, was never found). Tio Gordo’s restaurant is located here today. No guests or other employees died in the fire, but a volunteer firefighter (bystander)—Malcom Campbell—sadly did. (Port Huron Daily Times 1903: 02-18, p 5; 02-19, p 1; 02-20, p 7; 02-23, p 1; 03-29-1898, p 5; and various city directories.) See Figure 6.

Figure 6. St. Clair Hotel (Huron House), after the fire of February 18, 1903. (Port Huron: Celebrating our Past, 2006, page 116. The book caption errs in saying the fire was in 1904 and that the building was on Butler Street.)

1903 to 1911

The land of the project addresses had been cleared and remained vacant . . . probably.

1911 to 1990

311-313. The short history of these lots prior to the O’Hearne Block of 1924 is unclear at present. A news article from 1912 stated that O’Hearne was building a new vaudeville house/theatre next to the Gas building (315-317), but it did not specify north or south. There was a theater at the north side of the building for a long time, the Family Theater, but it does not seem to be O’Hearne’s since a theatre was already at that location by 1911 (“Electric Theatre” as shown on the 1911 Sanborn Fire Insurance map for Port Huron, LoC and the Michigan Room, St. Clair County public library). Also, when the 1924 O’Hearne Block was built, it was reported that a brick structure in the same location had been torn down. The 1912 article also stated that the new theatre would be a fireproof building of concrete, yet neither the existing theater nor the razed building were concrete. In any case, the present building, the O’Hearne Block, was built in 1924 for J. C. Penney, which remained in the structure until the fall of 1990, when the store moved to the Birchwood Mall. (The Port Huron Times-Herald 02-24-1912, pp 1, 7; 10-10-1924, p 14; and The Times Herald 10-04-1990, pp 1A, 10A.)

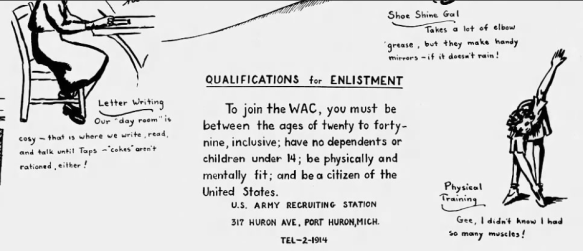

315-317. In 1911 construction on a new brick building at 315-317 Huron Avenue began, and was finished in 1912. This two-story building belonged to Port Huron Gas, which became Port Huron Gas & Electric. Wolfstyn & Co. clothing store shared the building. Having come into disfavor, Port Huron Gas & Electric was replaced by Detroit Edison in 1919. Detroit Edison remained in the building until August of 1941. After this time, the building was used for World War II civil defense business, like rationing and recruitment (see Figure 7), after which time it became vacant. Carroll House, a department store, moved into the building in 1948 and apparently did well until 1969, when the city tax assessment had suddenly about doubled. Not being able to handle that burden, the store closed.

Figure 7. A portion of a full page ad for the Women’s Army Corps, and as can be seen, 317 Huron Avenue was the recruiting place for this corps (The Port Huron Times Herald, April 13, 1944, page 10).

In January 1970, a small corporation purchased this building (along with 311-315) and allowed J.C. Penney to use the basement as its warehouse (its warehouse building was in the way of the planned-for parking lot behind the block). Eventually J.C. Penney took over much of the building and put up an aluminum facade in 1974, unifying the two buildings in a popular architectural facade style of the day. As J.C. Penney vacated the building in 1990, the facade was removed in 1992 and the building somewhat restored. (City Directory 1946-47, p 469. The Times Herald: 01-11-1970, p 5; 06-03-1974, p 2. Port Huron Times Herald: 02-19-1912, p 5; 08-22-1912, p 5; 12-31-1919, p 10; 09-28-1941, p 2; 07-16-1943, p 7; 01-01-1944, p 19; 09-19-1945, p 1; 03-10-1949, p 3; 03-05-1968, p 5.)

1998

The buildings are within the Military Road Historic District, being listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

Editorial Notes: This post was slightly edited on December 6, 2019, to make a correction related to four-story buildings in Port Huron. It was altered on December 11, 2019, to reflect the additional information that Bob Davis kindly shared–the 1859 image of the Huron House from the 1859 map of the county (found in note 3 below). Unless a person possesses a photographic memory, one cannot count on remembering everything–the author did not remember that the Huron House was one of those depicted along the border of the huge 1859 map. It is always best practice to check all possible sources . . . and perhaps check again!

Notes

1 This post is the result of original research done in November 2019, on a voluntary basis, for the purpose of discovering the historic uses of the buildings now occupied by Everything Classic Antiques and more. The information provided in the Military Road Historic District, National Register of Historic Places, was insufficient for the desired purpose. Virtually all information provided here is from original/primary sources; photographs are from both primary and secondary sources. All right reserved by author.

2 Among them, the White Block (burned in 1943), the Baer Building (burned in 1922), the Opera House (burned in 1914), the Maccabee Temple/Algonquin Hotel (neglected, then burned in the early 1970s), Bush Building (demolished in 1978), and the C. Kern Brewing Co. building.

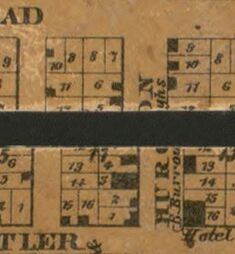

Very small section of the Port Huron subsection of the 1859 Map of Macomb and St. Clair Counties (Library of Congress. The black area is where the map had split apart). The key to Port Huron indicates that Burroughs was the proprietor of the Huron House, shown here in a different location (southeast) of where the Huron House was otherwise known to have stood.

3. If the subject of this article was only the Huron House, or even the historic hotels of Port Huron, the following information would be in the body of the text. The 1859 map of Macomb & St. Clair Counties by Geil & Jones (on file with the Library of Congress/LoC), shows the original Huron Hotel–at the opposite corner of Huron Ave and Butler St–and even has an image of the establishment. The building is obviously not the same one as that shown in the circa 1860 photo, and so the building was not moved. The hotel proprietor, Mr. B. Burroughs, is also different from the latter hotel’s proprietor on the west side of Huron Ave. Uncategorized structures are shown existing along the west side of Huron. A 1903 article (Port Huron Daily Times, Feb. 18, p 5) shared that the wood hotel was built about “40 years ago,” which would’ve been 1863 or thereabouts. For whatever reason, the hotel’s business location was moved.

Huron House as shown on the 1859 map of Macomb & St Clair Counties (LoC). This early version of the hotel was on the east side of Huron Ave., at Butler Street.

4 A note on the building’s ownership: When it was so expensively expanded in the 1870’s, a large group of local investors owned the Huron House: N.P., J.H., and E. White, Howard & Son, John Johnston, D.B. Harrington, John P. Sanborn, Wm. Wastell, Hull & Boyce, M. Walker, E. Fitzgerald, and L.N. and R. A. Minnie. When it burned in 1903, the owners were the estates of both James Goulden and Henry Howard. The insurance on the building was far less than the actual total loss, according to a 1903 article. From Port Huron Daily Times, 02-18-1903, page 5.